There are moments in the year that seem almost written in advance. Christmas is one of them. Long before the day itself, everything already seems mapped out: the songs that are repeated, the gestures that are anticipated, the clothes that are prepared, the silent expectations that settle in hearts. On Wednesday, December 24, during the Christmas vigil celebrated at Hekima University College, in its large chapel, the Christmas carols preceded the Mass in an atmosphere of shared joy.

Between eight and nine o’clock in the evening, the voices, the lights, and the collective fervor seemed to suspend time. This moment, awaited and fully lived, imposed itself as one of the most beautiful of the year. Spontaneously, deep within me, an exclamation imposed itself: Christmas, with its traditions, its magic, its surprises, and above all that spirit capable of bringing together and warming, if only for an instant.

Yet this joy did not close the year; it opened it differently. When the music fell silent, a deeper question imposed itself: what remains when the celebrations pass? What does a year become once its high points are over? Christmas, far from being an enchanted parenthesis, then revealed itself as a call to re-reading. Not a simple assessment, but a discernment: rereading what was lived, what was held, what was also wounded. A year is not understood only from its peaks, but from the memory it leaves and the responsibility it entails.

On a global scale, the year 2025 was marked by the persistence and multiplication of conflicts. In several regions in the world, notably in Africa, in Eastern Europe, and in the Middle East, armed violence continued to structure the daily lives of millions of people, recalling the persistent inability to durably prevent war. These conflicts, often old but revived by new power relations, shaped the year through their brutality, the banalization of human suffering, and the massive displacement of populations. In this context, the emergence or return on the international scene of political figures presenting themselves as mediators of peace, notably Donald Trump, generated as much hope as controversy, revealing how the quest for peace remains crossed by logics of power, strategic interests, and sometimes ambiguous political staging.

Alongside these geopolitical fractures, the year was also marked by transformations less visible but just as decisive. The ecological question and the green transition imposed themselves with renewed urgency in a world increasingly affected by climate disruptions and environmental inequalities.

At the same time, artificial intelligence experienced unprecedented expansion, inserting itself into the fields of work, research, governance, and even ethical reflection. Between promises of progress and legitimate fears, this technological acceleration posed fundamental questions about the meaning of development, human responsibility, and the place of the person in an increasingly automated world.

In this fragmented global landscape, Africa shared the same vulnerabilities, often in an amplified manner. The political and diplomatic reorientations of major powers affected international cooperation and the humanitarian sector, accentuating the precarity of many populations. Latent conflicts were rekindled, new tensions emerged, while the issue of refugees and internally displaced persons remained one of the most visible faces of the year. And yet, in the midst of these fragilities, the wind of Generation Z continues to blow across the continent, reminding us that Africa remains inhabited by a youth that refuses silence and seeks, sometimes in tension, paths of dignity and future.

In this already heavy picture, the situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo imposed itself as a particularly painful wound. From the very beginning of the year, the resurgence and intensification of violence quickly dissipated hopes for a lasting appeasement. Expectations of a return to peace gave way to deep disillusionment, while populations continued to live to the rhythm of insecurity, displacement, and mourning.

As the end of the year approaches, many celebrate Christmas and the holidays in an atmosphere marked by uncertainty, where joy mingles with anguish, and where hope relates more to inner resistance than to immediate promise.

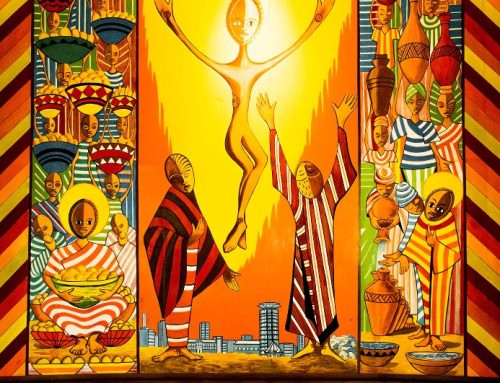

In this context, places of formation such as Hekima University College remain spaces of discernment where students coming from diverse African horizons learn to think peace, justice, and human responsibility from lived realities. For its part, the Jesuit Historical Institute in Africa, JHIA, recalls, through the work of memory and research, that rereading the present supposes rooting oneself in history in order to illuminate the challenges of the time to come.

This conviction found a particular echo during a meeting, in July, at Kenyatta University, where the historian Toyin Falola invited each person to tell his or her story. According to him, it is these modest and sometimes fragmentary narratives that constitute the true fabric of history. This invitation profoundly joins the mission of JHIA: to make space for voices, preserve traces, and refuse that history be reduced to only major events.

It also fits into a year marked, within the Institute, by times of pause and transition, notably a collective reflection on the African contextualization of the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius, as well as leadership changes, recalling that, like persons, institutions live through passages, necessary stops, and rereadings, where some things come to an end while others take shape.

As the year draws to a close, these collective rereadings inevitably meet more intimate questions, shared by many, even when they remain silent. How was this year lived, beyond calendars and major events? What held, and what collapsed along the way? What promises were not kept, what resistances emerged, what lessons imposed themselves without being fully formulated? For many believers, these questions are also accompanied by an interior evaluation of the relationship maintained with God, of fidelity in trial, and of the capacity to hope without withdrawing from reality. Resolutions for the coming year then appear less as artificial ruptures than as a way of disposing oneself differently before life, before others, and before God.

And if one were to conclude these reflections as everyone does, by simply wishing that 2026 be a good year, full of success, goodness, and promises? After all, words are easy, and the beginnings of a year lend themselves to it. Yet, at the end of this rereading, such a conclusion seems insufficient. Perhaps it is better to welcome the year that comes without slogans, but with the humble decision to remain attentive, responsible, and faithful to life, even when it unsettles, even when it demands more than simple wishes.

By Ella Mindja

Institute of Peace Studies and International Relations | Hekima University College