Pope Francis (1936–2025) has passed away, right in the midst of the Jubilee Year of Hope. It is undoubtedly a turning point in the history of the Society of Jesus—the story of a son of Saint Ignatius who, for the first time, was elevated to serve as the Supreme Pontiff. The first in history to come from Latin America. A great Jesuit, of course, born on the eve of the Second World War, at a time when authoritarianism (both left- and right-wing) and international fascism were on the rise—forces that his native Argentina would soon suffer under.

These political regimes tend to produce masses of the excluded, the persecuted, and the poor. Young Bergoglio grew into his Jesuit vocation in this environment and was later called to govern as Provincial of the Jesuits in Argentina during a politically and socially tense period, one that tested the unity of minds and hearts within both the Society and the Church, as it did for society at large. He was often misunderstood, yet always remained vigilant.

A few months before being appointed bishop, he published an article in the Ignatian Journal of Spirituality (CIS): “‘In Conformity with this Hope’ (Const. 812): Some Reflections on the Union of Minds and Hearts.” In it, Father Bergoglio affirmed that the union of minds and hearts builds up (edifies) the body of the Society of Jesus and the Church. By contrast, he warned that “expressions of dis-union and dis-unity, whether clearly such or disguised as union, are verified in and through desolation, produce desolation, disedify and cause degeneration in the basic self-identity of the Society.” At its most insidious form, this desolation consists in “believing oneself superior to others (‘I thank you, Lord, that I am not like this tax collector’).” It is nourished by resentment “at being sidelined, not consulted, or lacking influence in decisions,” as well as “by focusing on the faults of others and the community—or faults we imagine others have or project onto them.”

Such desolation “produces and feeds the spirit of ‘should-be’ (such-and-such ‘should’ be done, or this decision ‘should’ be made—when in fact it is often just an alibi for one’s own laziness or inability to act).” It ultimately reflects incompetence “or envy at a brother’s success or achievements,” and “stems from pettiness and avarice, from a lack of magnanimity and generosity regarding material goods, among other things” (143).

As an antidote to this culture of desolation, Father Bergoglio proposed a “return to that fundamental humility that places us before God, and therefore in the midst of our brothers and sisters.” This humility, he continued, “is the only valid and safe starting point: in it, self-renunciation takes place; in it, a person truly worships and venerates; in it, one experiences one’s own contingency, both in the history of the world and in the history of salvation” (144). This culture of humility/consolation stands in stark contrast to any kind of “triumphalist success in a particular space or place.” Rather, it is achieved through a transcendence, by which one rises to a higher level, “guided by loving hope.” As Father Bergoglio concluded, “The union of minds and hearts is achieved through hope in the Lord and in His Heart… It is achieved through daily, realistic work and labor, through apostolic courage in prayer and action (parrêsia) that frees us from the petty bonds of our narrow, selfish world, making us apostolically fruitful” (145).

Years later, at the beginning of his pontificate, the Church welcomed in Francis a Pope who had learned profound lessons from life’s hardships. He was a Pope humble enough to ask the people of God to pray for him before he blessed them from the central balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica.

He introduced himself simply as “the Bishop of Rome,” whom his “Brother Cardinals” had gone to fetch “from the ends of the earth.” His election as Pope did not make him better or superior to others. The Church of the peripheries he represented—now at the Roman center—had to rely on everyone if it was to succeed and move boldly forward; it had to be collegial.

The new Pope sought to be one with and among his brothers, all at the service of the praying People of God, listening and discerning together what the Holy Spirit is communicating to the Churches of our time. The new signs of the times included the ecological crisis, the migration crisis, the crisis of abuse against minors and vulnerable persons, and a crisis of hope for much of humanity—including within the Church itself.

Thus, Cardinal Bergoglio became the first pope to take the name Francis—yes, after Saint Francis of Assisi! One of the most influential saints in Church history, who preached poverty and humility, showed a remarkable care for the environment, and engaged in dialogue with those considered “Other.” Pope Francis embodied that same humility and openness. Like the Saint, he desired to live by the Gospel, to preach the Good News of joy and hope—especially to the poor and marginalized. He often expressed outrage at a world of abundance where everything seems interconnected, yet where the masses of poor and migrant people live first under the shameful indifference of the privileged, and then are scapegoated and portrayed as threats to humanity’s well-being and security (Crime).

Speaking about her brother after his election as Pope, María Elena Bergoglio admitted in a 2014 interview that his pastoral posture was not something newly adopted for convenience. It had always been at the core of his values. Her brother had been deeply marked by the scandal of seeing the vast majority possess so little, almost nothing, while a tiny minority hoarded everything in indifference and without scruples.

Through this reflection on consolation and desolation, a model of pastor emerges from Bergolio, —one forged in the fires of episcopal ministry— who decisively opts for the poor as the highest expression of the Gospel of Christ. This preferential option, broadly embraced by the Church in Latin America during his youth, was something Bergoglio often approached with nuance, both as Jesuit Provincial and as Bishop: less emphasizing radical, exclusionary ideologies, and more focusing on the radicality of Christ’s Gospel, which is for everyone (todos) and excludes no one.

Because it is from attitudes of domination, exclusion, and indifference toward the irreducibility of the other, and toward the sufferings of our neighbor, that abuses are born.

In the context of abuse, Francis reminded Church leaders that they are, above all, Shepherds—protectors of the littlest and most vulnerable. Speaking to the Chilean bishops, he invited them, in simple, direct language, to pastoral fatherhood: “If the shepherd goes astray, the sheep will go astray as well and will become prey for passing wolves. Fatherhood of the bishop with his priest, with his presbyterate! A fatherhood that is neither paternalism nor authoritarianism, but a gift to be sought. Stay close to your priests, like Saint Joseph, with a fatherhood that helps them grow and develop the charisms that the Holy Spirit has poured out upon your respective presbyterates” (January 2018).

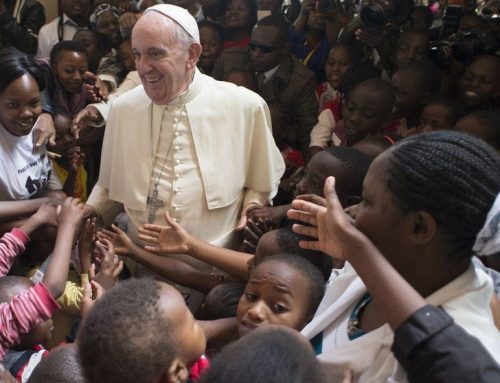

It is this same paternal and serving leadership, and the hope it carries for humanity, that the Church of God in Africa celebrated during the novena commemorating Pope Francis’s return to the Father of Heaven. Former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta summarized this humble greatness in a story he shared about the Pope’s 2015 visit to Kenya. Someone had insisted on meeting the Pope privately. After his own private meeting with him, the President presented the citizen’s request. The Pope agreed, asking the President to leave the room (his office) so he could meet with the person alone. The President joked about this “little coup,” but marveled even more at Francis’s method: his fatherly and humble touch. Once back in Rome, Francis continued to correspond with the individual he had met in Nairobi, showing concerns about his well-being.

These are gestures that speak to all humanity. This is the hope that sustains us now, as we pray together with our Cardinals for the election of a new Pontiff. For Pope Francis has died. Long live the Pope…?

Jean Luc Enyegue, SJ

Director of the Jesuit Historical Institute in Africa